The Klarna F-1: the price of money

A few weeks ago, Klarna publicly announced that they had filed a registration statement on Form F-1* with the intention to shortly IPO on the NYSE. Using the ticker KLAR (meh), the company was targeting a $15 billion - $20 billion valuation. We’ve been in a bit of an IPO drought during the past couple of years so this was exciting. IPOs are fun and kinda the end-goal for big consumer companies, so someone like Klarna going public is a good sign that things are getting better. Sweet.

If you know, you know.

Well. Hold your horses... We are very much not back, it turns out, because (God Bless America) a couple of weeks later, Trump announced a very memeable set of tariffs and Wall Street promptly vomited with stress. Understandably, Klarna rainchecked the IPO.

Not to make this about me… but I had already started trawling through the hundreds of pages that make up the F-1 so I decided to press on with this piece. After all, the interesting part isn’t really the IPO itself, it’s what we can uncover from a prospectus about a company.

So, Klarna.

As a general rule, I don’t like the Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) sector. I don’t think that most people need help buying more crap and I certainly don’t think that the majority of humanity is wise enough to use financing sparingly.

However, as a general rule of investing - and to risk over-simplifying the whole thing - it’s wise to invest in companies that are good at making money. From this point of view, Klarna is pretty appealing. Last year, it facilitated $105 billion in gross merchandise value (GMV), which works out as $2.8 billion in revenue and scraping into profit with $21 million in change. It boasts 93 million consumers, 675k merchants, and operates across 26 countries.

A lot of Klarna’s success is due to its incredibly tight value proposition: Klarna lets you buy stuff when you couldn’t previously. It’s telling that most of its customer acquisition happens at the point of purchase online, as it points to consumers acting in the moment rather than seeking it out as part of a well-thought through plan. Klarna also has benefited from a perfect storm of innovation over the last twenty years: the rise of smartphones and spread of ecommerce has made purchasing more accessible; globalisation has driven down prices (until now maybe); and incredible delivery innovation has made us less patient and more demanding as consumers. The rise of social media and influencers has, indeed, influenced us to buy.

But, as we know, the easiest way to make money is by leveraging people’s worst impulses. And this is what really what drives Klarna - because despite the strong value proposition and great timing etc etc - lending money to fund ill-advised choices has always been good business. It’s just not very warm and fuzzy.

And here’s the problem. Klarna wants to make money and be warm and fuzzy.

You’ve probably seen the cutesy branding and nice guy messaging, which is your first clue. Part of this is strategic: when you’re thinking about splitting your latest Zara haul into three payments, Klarna’s friendly brand is reassuring. It’s not a Wonga or a loan shark or a credit card - it’s just happy, bubblegum pink Klarna. This makes consumers feel better about using a BNPL service, because it doesn’t feel like one and that removes the fear / embarrassment / confusion / mistrust that might otherwise hamper the sale.

But, having gone through this F-1, I think there’s more to it than that. I think that Klarna is not comfortable with being seen as a traditional money lender. I’ll get into it in more detail later but, in short, the F-1 contains a juxtaposition of minimising aspects of the BNPL model while the numbers + metrics illustrate the importance these elements actually play. I think they (the leadership) aren’t just happy with the large amount of money the company ploughs through, they want it to be likeable and respected as well.

You’re sceptical, huh? Because it seems a bit silly that a massive, successful, oft-lauded company is… embarrassed about what it does?

Well, hear me out. This isn’t a new view on money-lending. It was centuries ago that Shakespeare wrote The Merchant of Venice and that’s a whole play that sparks from the era’s sentiment towards money-lending and how that translates to religious prejudice, dividing those that handle funds and those that are do not. Again, in Hamlet, the famous piece of advice from Polonius to his son, is “neither a borrower nor a lender be”. While we’ve certainly evolved these views, the remnants echo in our subconscious.

Companies are just a reflection of the people that run them - that’s why culture is so important because the beliefs and principles the team work by will shape your decisions in time. And if the people who run them are uncomfortable with what they do, then that will eventually trickle through.

Have a read. Let me know what you think.

*They file an F-1 instead of S-1 as it is a foreign company.

🔎Contents

The History of Klarna

How does it work?

The numbers

What’s the outlook?

….So?

💳 The History of Klarna

Twenty years ago, three fresh-faced Swedes took part in an entrepreneurship competition at Stockholm School of Economics.

The idea bombed. They came last.

Undeterred, the teammates, Sebastian Siemiatkowski, Niklas Adalberth, and Victor Jacobsson, pushed forward with the idea and, later that year, facilitated their first transaction via Klarna. The original idea was all about facilitating this new fangled concept of online shopping. In the noughties, buying off the internet was “nascent and marked by distrust.” Would the item be sent? How would it be delivered? Was it a scam?

“We started Klarna on this idea of ‘try before you buy,’ right, that was really it. So the credit was less about people borrowing money, it was more about the ability to touch and feel the goods before you paid for them.”

The early product allowed consumers to delay their payment so they could wait for the goods to arrive first (or the scam to be revealed, I guess). This reduced their risk and, in theory, spurred them on. When the online purchase did take place, the customers would ‘Pay Later’ and Klarna would pay the merchant in the meantime.While it sounds similar to today, being 2005 there were some big differences, notably that Klarna would snail mail the 30-day invoice to the customer. A different time indeed.

It was really an invoicing company at first and the key innovation was taking this tried-and-tested concept to the new but rapidly growing market of ecommerce. The late noughties was prime time for this sector’s growth, seeing the births of Amazon Prime, Shopify, Etsy, as well as the launch of the first iPhone. The growth of digital literacy and online purchasing was only accelerating.

Klarna was well positioned and grew in step. In 2010, they achieved $1 billion in GMV. In 2012, they hit the coveted unicorn valuation. From 2015 to 2020, the growth was explosive; Klarna grew their GMV from $6 billion to $53 billion, launched a suite of new products. By this point, of course, it was a bit more than invoicing. The early product had evolved into splitting a purchase into three or four payments (‘Pay Later’), needing to be less about online trust and more about money management.

The company also reinforced its operations at the same time, earning its banking license in 2017, a crucial step in their long-term strategy. Notably, it maintained profitability almost from the get-go, which was a rare and impressive feat that was only sacrificed when they moved into the US, choosing investment over profitability. Today, it’s the company’s largest market.

But nothing’s ever totally straightforward. The magic growth story faltered somewhat in 2021, when the company was a [willing?] victim of the 2021 tech valuation bubble. For one glorious summer, Klarna was lauded as Europe’s most valuable private tech company, held at an impressive ~$46 billion valuation. It didn’t last. The valuation was slashed to ~$7 billion only a year later, after a rough funding round. As tough a tumble as that was, the $46 billion was punchy and I’m sure everyone knew it. At today’s revenue, this would represent a ~16x revenue multiple and I’d estimate it as a 25 - 30x multiple in 2021. The IPO’s aim for $15 billion - $20 billion is both still an exceptional exit (aside for those who invested at $46 billion) and a realistic number.

And, there have been a few other hiccups.

An early switch from postal notifications to emails (which inevitably went into junk and were not read by customers) saw accusations that they were manipulating late fees. Two of the original founders, Jacobsson and Adalberth left. Rumours of governance conflict as Jacobsson having quietly built up his equity and exercising sometimes contrary voting rights along with it. An eyebrow-raising $2.6 million paid to Mrs Siemiatkowski’s organisations for their services. And more recently, the company was fined ~$48 million by the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority (SFSA) following an investigation relating to Karna's compliance with applicable anti-money laundering (AML) regulations.

Yet, in the context of twenty years, I think it’s swerved major controversies pretty well, especially given the divisive nature of the BNPL industry, where less illustrious companies, like Wonga, resided and ultimately failed.

Few industries have changed more than eccommerce in the last twenty years but consumer banking + fintech may be one of them: contactless* payments, phone app banking, instant transfers, Apple Pay, cashless shops. Klarna has uniquely straddle these two areas and managed to stay ahead and stay on top. There’s much to be admired in that alone.

*If you’re an American reader, then FYI this is what everyone else uses instead of signing a credit card receipt.

⚙️ How does it work?

Klarna has three different ways for consumers to pay or not to pay, as it suits you:

Pay Later

The big hitter. We’ve all seen the tempting offer as you hover at the payment page of the latest On Cloud shoe (the Pearl colourway, of course). Split this into three, four separate payments? Pay in 30 days? Go on then…

The product is “designed to be fee- and interest-free for the consumer” - designed being the operative word here because customers, who miss payments, can and do incur fees (but not interest for this product). As we will come back to later, these late fees accumulate hundreds of millions in revenue each year, so Klarna is somewhat betting on this fact.

Two things to note here: first, this product is the heart of the company still - despite the ‘we are more than BNPL’ chatter. Last year, Pay Later made up 76% of total transactions and 79% of their GMV. It’s what customers are using and so merchants are paying for it. Second, the importance of this product to Klarna’s growth cannot be understated. Klarna benefits from massive organic customer acquisition that mainly happens through Pay Later. This product is intrinsic to the company and business.

Pay in Full

This “instantly settles purchases at the time of the transaction.” Not revolutionary. I imagine this was launched so they could offer any type of payment, moving the company towards an all-encompassing suite of products.

Fair Financing

This works in a similar way to a credit card but it’s got a catchier (and highly subjective) name. It allows customers to wait it out even longer than Pay Later but notably for this product, Klarna charges interest rates on that borrowing. Not offered everywhere.

And other products you may not know about:

Manage your money

Klarna has technically been a bank since 2017, although I think there is a gap between getting a license and what we think of as ‘a bank’. At some point the two may reconcile here though as Klarna has started offering more ‘banky’ products in some (mainly European) geographies, such as savings accounts and a Klarna card.

The deposits from these savings accounts are important later for their cost base as they use these to fund their lending.

Shop and save

Klarna hopes to own the beginning and the end of the consumer journey by creating a platform where you can search for goods rather than simply interact with Klarna at the point of payment, when you’ve already found them. There is an AI assistant to provide you with ‘hyper-personalised… product recommendations” and boast that customers find the “best prices for products” via their search engine. Saving while you spend.

💰 The numbers

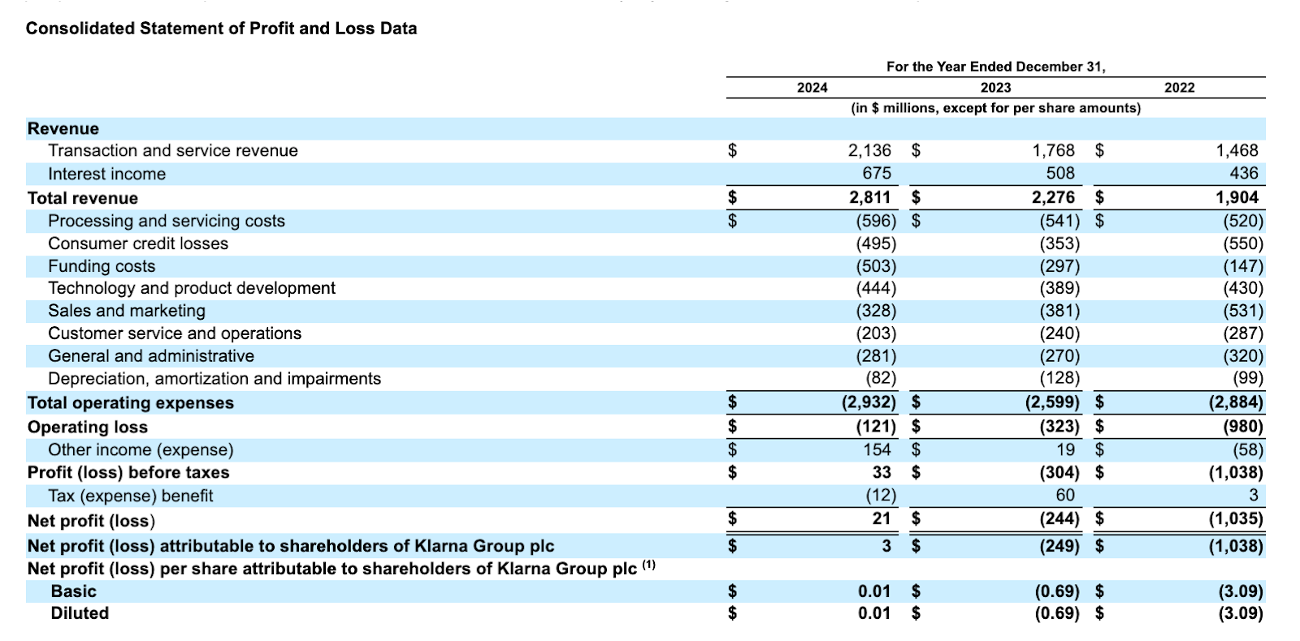

Klarna P&L from the F-1

Revenue

To make money, Klarna needs two things to be true: they need merchants to offer Klarna and they need consumers to buy using Klarna. And for growth, the company needs consumers to buy more because they can access Klarna financing.

Let’s break down the $$$.

Transaction and service revenue

T&S revenue is the main chunk of Klarna’s revenue, bringing in $2.1 billion last year. It splits into three streams:

Merchant revenue - What the merchants pay when consumers buy their products via Klarna financing and a few smaller, related fees. This makes up ~75% of T&S revenue for 2024 and is worth ~$1.6 billion each year.

Consumer service revenue - The fees that consumers pay and the majority of this (75%+) is made up of penalty fees i.e. the extra cost of getting behind with your repayments. This translates to ~$256 million in late fees alone. The rest of this is from subscription fees for Klarna Plus.

And the remaining ~8% or $170 million comes from advertising revenue. This one works the same as most platforms: brands pay for targeted advertisements within the platform.

Interest income

Interest income represents ~25% of Klarna’s total revenue at $675 million. The majority is from interest that consumers accrue when they delay repayment (like you’d get on a credit card) when they use Fair Financing - so, like with the fees, the charges for late payments are significant to the model. There’s also some interest from debt securities and other related fees to merchants.

Other income / expenses

Last year, this was $154 million and this turned out to be pretty crucial as it tipped the final numbers into positive net profitability, which - even if not part of the core business model - makes a good headline for the prospectus. This mainly came from a net gain of $171 million from the divestment of Klarna Checkout but was also then offset by the $47 million fine from the SFSA (alongside a few other bits and bobs to balance to $154 million).

Costs

They say it takes money to make money and that’s certainly true here with $2.9 billion in operating expenses. A lot of these are familiar categories that I won’t break down (sales and marketing, product development etc) but let’s pick out a couple of sparky points:

Funding costs

This translates to the interest that Klarna pays, for the money they use to finance products like Pay Later etc. As we know Klarna offers bank accounts and therefore can access funding from consumer deposits like a typical bank. These deposits are generally held for longer terms than Klarna lends money out (Pay Later is typically 30 days for example) and so they use these for a large proportion of the cash that they then lend out to other consumers. But, when you deposit money in a bank account, you generally get interest on it - and so it is this interest that we are referring to.

At the moment, this amounts to $503 million. It’s no small sum but is cheaper than they’d get by borrowing externally. On the downside, there is a lack of control with this cost - it will generally reflect the wider market and so is liable to fluctuate. On the plus side, the rest of the market is in the same position so it’s not a competitive concern.

Efficiencies

Across the F-1, Klarna is keen to remind us that - even if they are a retail bank or money lender or whatever - they are still also a tech firm and it’s likely because one of their key arguments is that they benefit both from the classic scalable tech model and the fast pace of innovation. Despite the mad amount of innovation in the last twenty years in this sector, the latter is not exactly a banking stereotype.

There are two areas where this is relevant to the costs: the first is that they are set up with a centralised product development approach, so they save money there even as they grow; the second is their use of AI. Let’s focus on the second.

The big AI push pre-IPO was publicly documented, by which I mean it repeatedly made headlines, as Klarna was one of the first large firms to notably utilise AI and - crucially - cut jobs from it. A lot of other places are testing it but fewer have made the savings that Klarna has. The company cut the workforce from 5,000 to 3,800 employees between 2023 and 2024, with plenty of quotes about the plans to further reduce this to 2,000 in the future. While I imagine the cuts were wide ranging, the narrative in the press was focused on how the customer services reps were being replaced with an (Open)AI assistant.

“We estimate that our AI assistant does the equivalent work of over 800 full-time agents (based on the average monthly reduction in chat and telephone conversations following the launch of our AI assistant) and delivered $39 million of cost savings in 2024.”

An ~8% cost cut in one year isn’t bad, especially when you consider the immediate costs of redundancies means that this saving will increase in 2025. It’s unclear where the next step reductions will come from, as AI is not yet in the position to be replacing other roles in completeness; the company’s indicated that they will effect this by not hiring and utilising the natural turnover but this is easier said than done.

Can they keep these efficiencies long term as they scale? Only time will tell.

🔮 What’s the outlook?

Profitability

The headline here is that the combination of growth and cost cuts means that Klarna is back to profitability. The subheading is that this was only made possible by the non-core ‘other income’ but given the trajectory of the cost cuts and revenue growth, it looks like ‘true’ profitability should be in store for 2025. This outlook is bolstered by the fact that Klarna, fairly remarkably in the context of how most ‘growth companies’ typically operate, managed to maintain positive net income all the way from 2005 to 2018, only taking a hit when entering the US market.

… Alongside growth

Klarna wants to show that the company can grow and remain profitable and I have to say, it’s a convincing picture that we’re looking at - especially as they dragged the numbers back from a billion-dollar loss only two years ago, all while building revenue. They say that they’ve hit the necessary inflection point and I believe them, even while I’m sceptical of the further cuts they aim for.

We flirted on this point before but one of the intrinsic growth drivers that this category benefits from - and Klarna is very good at - is the low cost of customer acquisition. A huge amount of their customers use Klarna for the first time, at the point of purchase online. It’s easy, organic customer acquisition that the fluffy branding only adds to when the customer hesitates.

Looking ahead, it’s my view that the continued, difficult consumer economic environment - potentially about to be a whole lot more expensive depending on where the next 90 days of tariff discussions land out at - will fuel this growth further. Brands still want to make money; people still want to buy. Klarna makes that possible, at a price.

…Alongside reputation?

But can it get the triumvirate: profitability, growth, and reputation as well?

Klarna certainly tries but I’m not convinced that it achieves this, given the fundamental challenges with the BNPL category. There are a few places in particular where it tries to soften the company’s image but these points often are undermined elsewhere.

Credit balances vs average order value (AOV). On the one hand, the F-1 boasts about the low average balance (“average Klarna of balance at $87 compared to the $6,730 average [US] credit card”) to highlight its positive position when compared the alternatives. But it also needs to tell a story about its potential to grow, which is literally the point of this document. So it outlines how it’ll increase its AOV by “retaining customers with increased loyalty”, which basically means getting customers to spend more… which would be likely to drive up the average balance over time.

The damn branding. If a picture says a thousand words then I’ll only add a few of my own here: these add neither value nor meaning to the prospectus. They are random, sickly sweet, and irritatingly vague. At best they are window dressing; at worst, they wilfully misrepresent what the company does. I don’t like it.

And finally, this dialogue around interest income. On the one hand, they are proud of how “99% of transactions conducted on our network were interest-free” and, in fact, connect it with overall growth as they believe that lower fees for financing actively drives consumers to choose Klarna, when they need BNPL products. The more consumers they get, the more merchants pick Klarna and Klarna benefits from the merchant fees.

And yes, there is a very small percentage of transactions that charge interest - which, remember, is different from late fees! - but those that do are very meaningful. As touched upon previously, last year’s income from interest brought in $675 million, which made up about ¼ of their total revenue. That’s a significant 1% of transactions. And when you consider that there’s also ~$256 million in late fees, suddenly it’s $931 million from late-paying consumers. Suddenly, these penalties seem to be a kinda important part of the model that they’ve slightly minimised earlier.

Ultimately, I think it’s hard to get away from how most consumers use Klarna for wants not needs. Opposite shows a diagram (from the F-1 itself) of the merchant’s signed up to it and let’s be honest, the majority of these are lifestyle brands. As much as I would like a new pair of sunglasses, you can’t classify buying from Ray-Ban on finance as a sensible financial decisions.

As Martin Lewis (British national treasure + Money Saving Expert) puts it: “it’s been sold as a lifestyle choice, not a debt, and pushed for instinct buys or even takeaways. Too many are in trouble with multiple BNPL repayments, leading to debt-chasing and credit file damage.” You can’t have it all and I don’t think Klarna is ever going to be able to separate itself from the wider industry issues while so much of their model depends on their BNPL products.

⚡️So…?

Imagine this. You started this fun little company twenty years ago with your university friends. It was all about the internet and helping small businesses online. You felt good. You realised really early how big the internet and online shopping was going to be so it was cool to be part of that big growth. You were helping connect buyers and sellers online in a safe way.

But today, everyone is ok with online shopping. You’ve built this big company and because the whole trust thing has really been solved, regular joes use your products to buy things. Things maybe they can’t afford right now?

Such is human nature that it isn’t so much we want to be proud of what we have achieved but we want to be recognised by other people for it. I know this to be true and if you tell me otherwise you’re a Buddhist monk or you’re lying. After all, if you build a business in the woods and no one is there to tweet about it, did you build anything at all?

This is what I think is at the crux of the issue here. They’ve built this fuck-off big money making machine. It’s a hell of an achievement by any standards. But imagine how it must feel to do all of this and then have to face the constant challenges to defend the company or talk about the BNPL sector or talk again about how they are trying to do it in the nicest way possible. I bet it grates on them. Because it’s not - let’s face it - a morally perfect company or close to it and they know it. It’s the price of all that money.

At the start, I referenced a line from Hamlet that picks up on the prejudice, even centuries ago, of money lending. But the rest of the speech chimes here as well:

“Neither a borrower nor a lender be,

For loan oft loses both itself and friend,

And borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry.

This above all: to thine own self be true,

And it must follow, as the night the day,

Thou canst not then be false to any man.

Farewell. My blessing season this in thee.”

To thine own self be true.* My strong belief is that the most successful companies (and the most successful people) are those who are at clear-eyed and content with what they are, good or bad. Klarna - regardless of my personal views - frustrates me as an investor because I think it’s a successful business that is hamstringing itself. To me, this is a long-term weakness of the company. I’d be fascinated to know how this discussion around reputation is addressed internally. I suspect this issue is incredibly divisive: some happy to make money and others plagued by guilt… but not quite enough guilt to quit.

There’s an elegant irony to all this. The growth relies on greed but the business is hampered by vanity; the desire to be admired. Yes, it’s a good company: large, profitable, and growing and I imagine it will do well at the eventual IPO because, as we know, lending money to fund ill-advised choices has always been good business. But longer term it needs to get comfortable with who and what it is and tackle this in a better way - ready for the extra scrutiny that public companies inevitably face.

It’s a shame about all that shame. That’s the price you pay, though.

*Those familiar with Hamlet will appreciate an extra irony in this quote as Polonius is a sneaky little snake and dies when he is busted spying. Good advice but terrible example of these principles.

Sources

https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/2003292/000162828025012824/klarnagroupplcf-1.htm

https://www.ft.com/content/29ab1588-58bf-11e2-bd9e-00144feab49a

https://www.klarna.com/international/about-us/

https://www.ft.com/content/9b120706-17eb-46c2-983d-53cf1e2f88fe

https://www.ft.com/content/9f73b352-723f-471b-b098-5f090279b5bb

https://www.ft.com/content/66b65d68-d62e-4aec-a1ad-a7d9e2ba0435

https://www.ladbible.com/news/uk-news/martin-lewis-mse-klarna-buy-now-pay-later-961673-20241023

https://techcrunch.com/2020/12/08/making-sense-of-klarna/

https://www.creativereview.co.uk/klarna-brand-refresh/